It helps a lot with your planning if you have a kind of outline with some rubrics to guide you through the process. Here’s the lesson plan I’ve been using, along with many other teachers.

Taken from: Dringó-Horváth, Ida; Fischer, Andrea (szerk.) Tanárjelölti kézikönyv. Budapest : Patrocinium Kiadó, (2015, 2019)

| Date: | Teacher: |

| School: | Group: |

| Group profile: | |

| Topic of the lesson: | |

| Content Aims and Objectives: | |

| Intended learning outcomes: (By the end of the lesson the learners will…) | |

| Special skills Development: (thinking skills;-metacognitive skills;-social skills) | |

| Teaching materials: | |

| Anticipated problems and possible solutions: |

| Time | Stage | Procedure | Stage Aim | Interaction Patterns | Skills | Materials | Comments |

- Extra activity (if there is time left):

- Handouts/Additional material

A lot of us think: “Why should I bother with such detailed descriptions?” and just skip the beginning. Here are my reasons why we should consider these as well – if not before every lesson, but at least every now and then.

Group profile

When planning a lesson, you have to take into consideration who your students are and at what level they are. As with hiking you wouldn’t like to grab a nursery-school or pensioner group up with you to Mount Everest, similarly during your lessons you wouldn’t like to teach politics to primary school children, and wouldn’t necessarily ask an 18-year-old about their favourite toys. Also there are differences in their interests and general language skills based on what type of school they go to – one of the best grammar schools, a “normal” high school, or a vocational school. So when thinking and writing about your group, you should consider the following things:

- What age group is it? = What kind of topics will interest them? What kind of topics will they be familiar with? Have they ever been to a restaurant / car mechanic / whatever? Do they have this experience in their own language or shall I show how it works?

- What level are they? How much do they already know? = How complicated can my instructions be? What kinds of words and grammar will they be familiar with? How developed are their language skills?

- How many lessons do they have a week? = Do I have enough time to plan more practice tasks or do I have to “hurry” things so that we can get to the end of the book during that school year?

- How motivated are they? Why are they learning English? What’s their aim with English in the future? = Is it something they have to do but hate doing it, or are they preparing for a language exam or for studying abroad? How active will they be during my lesson? How much nagging will I have to use to make them say something?

- Are there more boys or girls? – Again, in some cases different topics will be interesting for boys and for girls. Boys will probably like to talk about football and can be a bonding topic with their male teacher, but there might be some girls who are crazy about sports as well and we should never forget about them. If you know your students well, you can gather the topics they like talking about, and the topics with which they need more help.

- Are there any “problematic” students? = Do I have to differentiate? Do I have to pay more attention to any of them? Does any of them require my attention all the time? Are there students who cannot tolerate each other? How can I solve that situation?

Topic of the lesson

Basically, this is the line where you write what you want to teach, using a very simple sentence. In your lesson you have to focus on teaching only one thing, the other tasks will either lead to it, or practice using it in different ways.

Content aims and objectives

Here you list the most important aims and objectives, namely why you want to teach and practice the things you’re going to work with. For some ideas, look at the part where I deal with the aims and objectives in more details.

Intended learning outcomes

This is where you summarise what you want your students to take home at the end of the lessons. What are the things they’ll have learnt, practiced or deepened their knowledge in? You have to use a simple statement and focus on outcomes that you can measure. If you want to learn more about it, Google “Bloom’s taxonomy” and you’ll find a lot of interesting articles about it.

Special skills development

Here you can think of the different social and thinking skills you’re going to develop with your tasks during the lesson. Usually when we plan pair or group work tasks, we mainly develop students’ cooperation, understanding of others’ needs and tolerance.

What are the different thinking skills? Here’s a quick summary to help you with some key words:

Thinking skills = the mental processes we use to do things (e.g.: problem solving, making decisions, asking questions, making plans, passing judgement, organising information, creating new ideas; remembering, applying, evaluating)

- Creative: imagine, invent, change, design, create; unique, original, different; curiosity

- Critical: analyse, breakdown, compare, categorise, list, sequence, rank

- Cognitive: information gathering (sensing – seeing, hearing, touching + retrieving – memory skills)

- Metacognitive (thinking about thinking): reflecting, thinking out loud, learning to learn

- Basic understanding: organising gathered information, forming concepts, linking ideas together

- Productive thinking: using and understanding information, creating, deciding, analysing, evaluating

- Strategies: decision making, planning, problem finding, approaches, questioning

First they may seem a bit complicated or scary, but if you focus on the key words, they’ll gradually become clearer.

Let me give you some examples:

With a lead-in task we either want to raise students’ interest or gather their previous knowledge. With the first, we need their curiosity = creative skill. With the latter, we try to retrieve some information from their memories = cognitive skill.

With a production task, like writing a letter, we mostly want them to imagine a situation (= creative); brainstorm and gather their ideas, previous knowledge (= cognitive); plan and organise these ideas into different sentences and paragraphs (= strategic); apply the knowledge they’ve already learnt by writing the task; and finally check it (= evaluating).

Teaching materials

This is a list of the different books, workbooks and other materials that you would like to use during your lesson. (When mentioning the title of the book you’re working from, don’t forget to include the level as well.) This rubric can serve as a quick reminder of all the things you have to take in when you go into your lesson.

Anticipated problems and solutions

Again, when you go hiking, you have to consider what you will do if your road is blocked. Similarly, in a lesson you need a Plan B if anything goes wrong. When thinking these over, you should also imagine the situation that you have to be substituted by one of your colleagues. Most often, teacher trainees come up with anticipated problems such as “The laptop might not work, there might be technical problems”, or “Odd number of students versus even number”. I’m not saying that these are not real problems that can come up in your lesson, but the first one is the kind of problem that is impossible to solve in the lesson – you won’t go running around looking for another laptop, or go and solve the technical problem. The only thing you can do is just let it go after trying to bring life back to your laptop for a few minutes, and if you’re not well prepared, just improvise. And the odd number of students – this is such a basic situation that doesn’t need too much consideration – create a group of three. I very often see that the teacher undertakes the task of the partner, which might be an interesting experience sometimes (you realise that the task you’ve set is much easier or much harder than you had anticipated before your lesson; you can really see the different skills, vocabulary and grammar that students need to be able to solve that task, etc.), and might work now and then, but on the long run when you’re working with one student only, you cannot pay attention to the others who might need your help – so, I don’t really recommend this solution.

What kind of problems should you think over before your lesson? For me, the most important pieces of information would be about the students. Is there someone with learning difficulties? If yes, what works best with them? Is there someone who’s over-enthusiastic? Will they get hurt if I don’t work with them all the time but try to pay attention to the other students? Who is the student who is too shy but otherwise brilliant and I can rely on when no one knows the answer? All in all, are they co-operative with each other and / or me? If not, what can I do?

The second most important problems would be about their understanding. What shall I do when they don’t understand something? What kind of students are they – visual or audio? Should I start to draw to make them understand something or give more examples? Or shall I simply use L1 for clearer instructions or explanations?

Also, students are humans as well, and they might have a difficult day – they might be too tired, or too wound-up so they need a different approach to get into the mood of working. What should I do then? How can I make them co-operate? After a while, you get to know their time-tables and will know when it’s a problematic day for them, and you can come up with a Plan B if it’s the case again.

I tried to suggest between the lines, but with the anticipated problems it’s never enough just to list the problems – you need to provide a kind of solution. A solution that works most of the time. It might not work this time, but at least you provide some ideas for yourself (and your imaginary substitute teacher) on the base of which you can start to solve the problem.

The different stages

This is the part where we decide on the best order to do the different tasks we chose in the planning part.

When we plan a lesson, we have to divide the things we’re going to teach into three categories, because the stages you’re going to use will differ with them. Basically, we practice receptive skills (reading, listening), productive skills (writing, speaking), and teach new vocabulary and grammar.

Probably the “easiest” ones are the receptive skills – they’re kind of passive skills, where students just receive something, as opposed to the more active skills, the productive ones. For most of us it is much easier to get a present from someone than to give. With the latter, you have to find out what kind of present you want to give, where you can get it, you have to go and buy it, then wrap it up nicely (definitely the most difficult step for me), and then find the time and place to hand it over.

Reading & listening

So, let’s start with practicing the receptive skills. I’m deliberately using the word “practice”, because in the case of English we don’t have to teach them how to read as they use the same alphabet as we do, and with listening basically if you can hear you’ll hear what is said to you, but students have to practice a lot to make the most out of it, to find the meaning behind the strange words and strangely sounding speech.

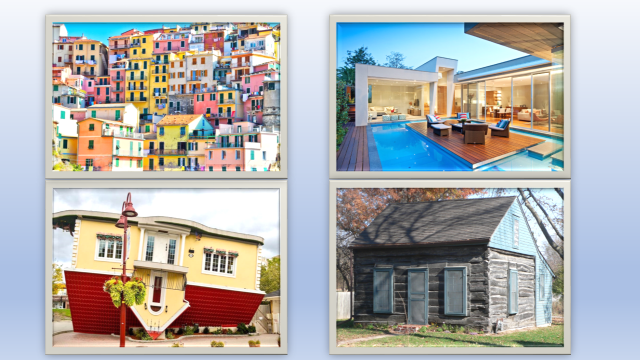

When practicing these skills, we use the pre-, while-, post- approach. First we give them some pre-tasks with which we mostly try to raise their interest in the things they’re going to read or hear about, and also we try to gather what kind of previous knowledge they have that they can use to enhance their success. In an ideal world our students will do anything happily we ask them to do just because they are good students, but in real life it is very rarely so. Therefore, it is our task to give them some meaningful purposes so that they will want to work with the task. The most idealistic thing is to raise their interest and curiosity in the topic we’re working with. The most successful one can be some pictures, as they imitate real life the most. Course book writers themselves work with this method as you can find a lot of pictures in the books, but these tend to be somehow small and this way it’s not always too easy to make out what they want to show. However, with the projector you can make wonders. If the students can see more detailed, and maybe more interesting pictures in the given topic, they are more likely to become motivated to discuss them, and finally more interested in the topic they are leading in. One of my most memorable teaching experiences is the lesson when I discovered how much wonder four colourful and hugely projected pictures can make. We all know the task: “Look at the four pictures of different houses. Choose the one which you would most like to live in.” If the pictures are small, or photocopied black and white pictures, the students will imitate some talk, but it will mostly be about trying to make out the details. Which is not bad, either, but somehow not lifelike. For the task I chose the following pictures:

The sources of the pictures: https://www.loveproperty.com/gallerylist/74994/50-of-the-worlds-most-colourful-homes; https://www.idesignarch.com/timeless-modern-residence-with-stunning-lap-pool-and-floating-deck/elegant-modern-home-with-integrated-swimming-pool-australia_1/; https://www.rd.com/article/upside-down-houses/; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bellevue,_Nebraska_log_cabin_from_SW_1.JPG

After projecting them (and in that classroom the pictures covered about half of the wall), my students started talking without even listening to the instructions. I let them did that for some minutes, because I could hear them talking excitedly about the houses in English. “Oh, look at that house! What can it look like inside?” “Oh, look at that swimming pool and huge windows! I’d really like a house like that.”, and similar sentences. When the first excitement died down a little bit, I could finally tell them my task: “Imagine that you’re going to university in another town with your partner and would like to rent a place to say together. Money doesn’t matter. Which one will you choose and why?” And the pictures were so interesting that they kept discussing them for 5 more minutes. After the discussion, we listened to the pairs’ choice (the boys chose the last one because that’s the least expensive; the girls immediately corrected them that money didn’t matter. J), read about other unique lodgings, and wrote a short ad about one of the places as if it was them who wanted to offer the house for rent. After this lesson and realisation, I started to work more and more with pictures and started to organise them into ppt-s and use unique and interesting pictures to raise their interest. It works most of the time.

After getting over the pre-task(s), we can start to focus on the while-tasks. Most often, we would like our students to read or listen to something twice, giving 1-3 general questions first, then going into more details (scanning vs. skimming; listening for gist vs. for specific information). Having done these tasks, with listening it is mostly useful to read the transcript while listening to the track again; this way students can get a deeper understanding of the text, can identify problematic words that they probably know just didn’t recognize it in the spoken language; or just get used to the specialities of connected speech (intonation, stress pattern, etc.). When choosing a course book, it can be a guiding factor to choose one where the transcripts are included in the student’s books as well, but if it’s not the case, you can always project it from the teacher’s book (or photocopy it for the students) (= listening in detail).

And now, the post-tasks. This is what some teachers just leave out, either because of time problems, or they don’t find it useful enough. However, in my opinion, this is just as important as the other tasks and gives a very good opportunity for students to formulate their opinion or work on the productive skills. It can be a simple follow-up discussion or a more complex task where they have to use the information or new words / expressions from the text.

Speaking & writing

As it was somehow implied in the previous part, productive skills sort of stem from the receptive skills, either by imitating the things we read or listen to, or leading them in or following them. As nothing will grow (apart from the weed) if you don’t sow, likewise students won’t be able to produce anything if you don’t show them how they can do it. Teaching speaking and writing, on the other hand, is so complex, and so many good methodology books have been written about them, that I don’t think I can summarize their place in a lesson plan very shortly. If it is a well-planned lesson, your students will speak and write at some points, but whether it is just simple repetition or drilling, or getting to the communicative end of the spectrum, will depend on the level of your students, the type of the lesson and the tasks, and the willingness of your students to produce anything. In some cases, the pre-, while- and post- approach might work with writing, but with speaking you need to focus on whether fluency or accuracy is in the centre.

Vocabulary & grammar

When teaching vocabulary and grammar, we use the PPP (= presentation, practice, production) approach.

As with the skills, we want to teach them functions and typical situations where they can use the newly acquired grammar and vocabulary. To set this context, first we have to show them what we want to teach with a short listening or speaking task and take out the typical sentences which contain the grammar point or the new vocabulary. After presenting these examples, we can let students draw conclusions, formulate the rules or explain the meanings of the words somehow.

Next, we have to make our students practice these with different tasks. First we would like full control over their work, so that they learn these accurately. For this, drills and translation tasks are highly useful, as well as the different tasks (e.g. complete the sentences) in the books and workbooks. The next step will be the semi-controlled part, and finally the free practice.

When we’re sure that our students can use these grammar points and vocabulary items correctly, we can make them produce something – like a short dialogue, a piece of writing, a story, etc. using the newly learnt structures.

Summary

As you can see from the above description, we cannot focus on only one of the skills during our lesson, as they all somehow overlap. They get written or spoken language examples first to learn new words and / or grammar structures; they speak or write to practice using them or to produce their own ideas. So if you follow these steps, you’ll have a nice balance of most or all of the different skills needed during learning a language.

Procedure

This is the place where you can summarise in a few (really, one or two) simple sentences or instructions how you want the tasks to go. You can find some more ideas about the instructions later on.

Objectives

If you have a good teacher’s book with not only the solutions to the tasks but with a rather detailed lesson plan, it will tell you why you should do the given task and what you can achieve by doing it. I have collected some useful expressions that these teacher’s books use:

- to present ways of …

- to present some …

- to introduce the topic of …

- to activate Ss background knowledge …

- to give Ss practice in using …

- to revise …

- to help Ss make predictions about the reading / listening text based on visual prompts

- to give Ss the opportunity to elaborate on the topic of the text

- to have Ss differentiate between …

- to provide Ss with a sample for …(e.g. writing a description)

- to raise Ss’ awareness of certain structures that can be useful when … (e.g. writing a description)

- to help Ss revise …

- to encourage learner autonomy

- to give Ss the opportunity to check their progress

(H.Q.Mitchell: Full Blast! 2, MM publications)

Skills and sub-skills

In a nutshell, after deciding on the tasks, it’s advisable to think over the different skills and sub-skills we would like our students to practice and improve. This will help to see whether the tasks are really aimed at those skills we would like to work with, and also to see the balance of our lesson. You can find a chart seeing what the different subskills are in the next part. Later on, I’ll post a more detailed description of the subskills with some example tasks.

Key words

When formulating my lesson plan, I use the following chart to help me with the wording. It’s a summary of the different skills, sub-skills and stage aims – although this latter part is just a short collection of some general ideas, it can be altered to our needs.

LESSON PLANNING RUBRICS

for wording Stage Aims and Sub-skills

| Stages | Aims |

| Starting, saying good morning | create the atmosphere, welcome |

| Warmer | ease, focus |

| Lead-in | refresh, set context |

| Presentation | introduce the topic or any new material (grammar, vocabulary etc.) |

| Practice (controlled, semi-controlled, free) | practice: understanding a new text, reading for specific information, exchanging information, etc. |

| Production | make Ss use the target L, have a discussion in E, deepen, become able to |

| Pre-reading/listening | raise interest, gather Ss’ previous knowledge, become motivated to |

| While-reading/listening | experience, identify |

| Post-reading/listening | become aware of, broaden, expand |

| Checking | summarize, draw a conclusion, exploit, reflect |

| Evaluation, Feedback | take a liking to, praize, encourage further practice, help them learn from mistakes |

| Setting homework | make Ss prepare for the lesson, deepen their understanding, consolidate |

| Farewell | learn… |

| Skills | Sub-skills | Skills | Sub-skills | |

| Listening | for gist (global understanding) | Writing | organisational | |

| for specific information | editing | |||

| in detail | summarising | |||

| recognition of connected speech | paraphrasing | |||

| deducing meaning from context | Speaking | pronunciation | ||

| intensive | using stress, rhythm, intonation | |||

| inferring attitude, feeling, mood | using the correct forms of words | |||

| predicting | word order | |||

| Reading | skimming (general, main ideas) | using appropriate vocabulary | ||

| scanning (for specific information) | using the appropriate register | |||

| deducing meaning from context | building an argument | |||

| note taking | fluency | |||

| proof reading, editing | accuracy | |||

| inferring attitude, feeling, mood | using functions | |||

| predicting | turn-taking skills, responding, initiating | |||

| repair and repetition | ||||

| relevant length |

Interaction patterns

The different interaction patterns can be frontal, whole group, group work, pair work and individual work. Frontal work is mostly used when the teacher explains some rules and the students listen to him / her (T – Ss). A whole group activity can be a discussion in which the teacher takes an active part as well (T & Ss).

Group work and pair work are similar – the students work together in solving some tasks or discussing their ideas (Ss – Ss; S – S). It’s advisable to go for groups of 3 or 4 when it’s important to gather more background knowledge – this way more students’ ideas will be included in the final outcome of the task. The disadvantage might be that not all of the students are similarly active and some of them might get less chance to speak. This is where pair work is more ideal as the students get the same chance of speaking for about the same amount of time. (Although some students will still be left out because they are shyer or think they have little knowledge or little to say. In that case you can use a more controlled way of speaking – one student should speak for 1 or 2 minutes, the other just listens, then they swap roles).

Individual work is when the students read or listen to a text or complete some grammar tasks and they don’t share work with the others. Ideally, this should account to the least amount of time in a lesson, as most of these tasks can be done at home as homework practice.

Creating pairs or groups

In a language lesson we often ask our students to create pairs and small groups to work together. I usually let them work with the person / people sitting close to them and very rarely create new groups. There are a lot of advantages and disadvantages of this method as well as forming new pairs or groups.

On the one hand, when the same people work together all the time, they develop a kind of relaxing atmosphere in which they can make mistakes and tolerate the other. However, after a while they can get used to their partner’s speech, this way they meet the same kind of language problems (pronunciation, grammar mistakes, etc.) again and again. Moreover, after a while they will know a lot about the other person and get bored with each other. When one student is much better at the foreign language or much more talkative, the other person might fall behind because of lack of encouragement from their partner or lack of opportunity to practice. Sometimes it is difficult for the students to “say goodbye” to their partner and look for other people to work with, so that’s the point where the teacher has to interfere and create new pairs.

There are similar advantages and disadvantages of group work. Once I had a demonstration lesson when I created the groups randomly at the beginning of the lesson. As this was the first time I did so, it didn’t go as smoothly as I had planned, and the people getting into the same group were so happy to be working with new partners that there were a lot of discipline problems. However, if you do it from time to time, after a while it shouldn’t cause any disturbances for your students.

Here are some ideas how to form new pairs or groups:

- Standing in a line: You can ask your students to create a line based on a criteria beginning from the lowest to the highest, e.g. their height, the months they were born in, the number of hours they spend on the internet each day, etc. It’s also a good warmer as with most of these tasks they have to speak a little bit with each other to be able to create the right order. When you’ve got your line, you can appoint the students into groups – like the first, second, etc. 4 working together; or giving them numbers.

- Using pictures: You can choose 4-5 different pictures from the same topic, and photocopy them in the number you need in each group. The students pick one at random and have to find those who have the same picture. Then they can work together. Again, it’s a good speaking task as well as they have to describe some important aspects of their pictures.

- Using questions: You can create a short “Find someone who…” type of task and then the people with most shared answers can work together.

- Picking something: When your students are at a more beginner level to talk this much or you don’t want to spend too much time with forming the pairs, you can take in any colourful things like little pieces of paper, strings, bottle tops, etc., and your students pick one at random. Then the students with the same colour will work together.

Materials

In this column you should list the different materials you use. If you work with the course book or the workbook, include the page number and the exercise number here. If you use some handouts or online material, write some notes here so that you’ll know where to turn. Basically, it’s the most important guide for you so that you’ll know after a quick glance how to proceed without having to read the other longer parts.

Comments

This is where you can write the comments for yourself, e.g. what kind of anticipated problems might arise and what you’ll do then; what you’re planning to do while the students are working with the task (e.g. prepare the next task, monitor them closely); etc. When I have demonstration lessons, I usually leave this column empty and then the teacher trainees can take their notes here – or even I can jot down my ideas during the lesson.